日本は今月下旬、第二次世界大戦後の政策規範を打ち砕くような、新しい国家安全保障・防衛戦略を発表する。東京は、1976年以来実施されてきた非公式なGDP比1%という上限を破棄し、今後5年間で防衛費をほぼ倍増させる計画を発表する予定である。また、北朝鮮や中国の領土内を攻撃できる長距離精密攻撃巡航ミサイルの取得計画を打ち出し、戦後の軍事力投射の制約を緩めることになるだろう。また、1967年に初めて採用され、2014年に緩和されたものの、ほとんど効果がなかった防衛装備品輸出の制限の多くを撤廃する意向を示すかもしれない。このパッケージが実施されれば、憲法第9条に根ざした日本の防衛政策の漸進的な変化の伝統を打ち破り、最終的には日本の防衛態勢と日米同盟を変革することになる。

この変化を促すのは、日本の政府関係者が「米国占領時代以来、最も厳しい」と語る地域の安全保障環境である。中国は徹底した軍事的近代化計画を進め、東シナ海で日本に対する海洋的圧力を強めており、尖閣諸島周辺海域には中国沿岸警備隊がほぼ常時出没している。8月の台湾周辺の軍事演習では弾道ミサイルの発射が行われ、日本の排他的経済水域に着弾したことから、台湾海峡での紛争が日本の安全に直接影響すると強調した。北朝鮮は核兵器やミサイルの開発を進め、10月には中距離弾道ミサイルを発射し、日本を通過させました。また、ウクライナ侵攻後、東京がG7に加盟してモスクワに制裁を加えた後、ロシアは日本を「非友好国」と位置づけ、日本付近の軍事活動を活発化させた。

特にロシアのウクライナ侵攻は、変化を加速させるものであった。日本の関係者は、キエフが困難な状況でも戦う意志を示したことで、NATOの支援が強化されるのを見守った。日本の防衛力を強化することで、米国をはじめとするパートナー諸国が危機的状況に陥ったときに、日本を助けてくれる可能性が高まるという結論に達した。岸田文雄首相に防衛戦略を助言する有識者会議が11月に記したように、「自分たちの国は自分たちで守るということを示すことは、同盟国や同じ考えを持つパートナーからの揺るぎない信頼を維持するために不可欠」(筆者訳)である。

日本国民もこれに同意しているようで、防衛予算を増やし、攻撃能力を獲得する計画に対する国民の強い支持がある。これは、日本が困難な状況にある近隣諸国に対する認識を反映した、過去からの逸脱でもある。2015年、安倍晋三元首相が自衛隊の役割と任務を拡大する法案を国会に提出し、攻撃を受けている同盟国を支援することを初めて認めたとき、新法は憲法に反し、戦争への道を歩むことになると懸念する国民がいた。今月発表される予定の政策変更には、そうした反応はない。

岸田内閣が戦略を発表するとき、いくつかの問題が注目される。

重要な課題 中国

国家安全保障戦略(NSS)は、日本が直面する安全保障上の課題について、「パワーバランスの変化が国際政治の力学に大きな影響を与えている」と指摘し、微妙な表現をしていた。その中で、日本が懸念する地域の第一に北朝鮮を挙げている。尖閣諸島をめぐる摩擦の高まりを背景に、2013年の戦略では中国の行動を "日本を含む国際社会にとって懸念される問題 "と表現しています。

日本の新NSSは、日本が直面する課題として、北朝鮮やロシアを差し置いて中国を第一に挙げる可能性が高く、台湾海峡の平和と安定に対する日本の関心や、現状を一方的に変更することへの反対を初めて明示する可能性がある。しかし、この戦略では、中国を脅威と表現することはないだろう。岸田内閣は、北京との「建設的で安定した」関係を求める政策アプローチを打ち出し、抑止力強化のための措置と、日本にとって最大の貿易相手国である中国の立場を反映した緊密な経済関係への支援を両立させることにした。岸田は先月、バンコクで習近平と会談し、ハイレベルな二国間経済協議の再開に暫定合意したが、これはこのアプローチの現れである。国家安全保障戦略では、北朝鮮やロシアが日本にもたらす脅威も取り上げられるが、初めて中国が焦点になると思われる。

Also of interest will be the language Japan uses to describe relations with the Republic of Korea (ROK). The NSS, released at a time of relatively warm relations between Tokyo and Seoul, described the ROK as “a neighboring country of the utmost geopolitical importance for the security of Japan. . . . Japan will construct future-oriented and multilayered relations and strengthen the foundation for security cooperation with the ROK.” A decade later, ties between the two are on shakier ground, but the geopolitical imperative of closer ties remains—and since the inauguration of South Korean president Yoon Seok Yeol in May, the Biden administration has pushed an aggressive trilateral agenda.

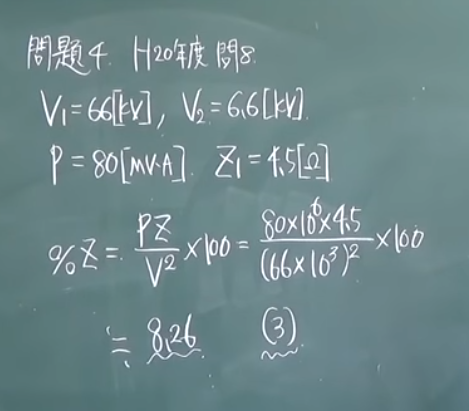

Defense Budget

Japan is poised to undertake increases in defense spending that are unprecedented in the postwar period. Through a combination of growth in core defense spending and other “national security-related” investments, the new strategy is likely to establish a budget trajectory that will approach 2 percent of GDP by the end of the five-year plan—from about 5 trillion yen ($37 billion in today’s exchange rates) in this fiscal year to as much as 11 trillion yen ($81.5 billion) by Japanese Fiscal Year (JFY) 2027. Press reports indicate that the core defense budget could total about 43 trillion yen over five years—an increase of more than 50 percent over the current plan. Other categories of spending—such as the Coast Guard, some civilian research and development, and public infrastructure—are likely to be included in the total calculation, as part of a new “comprehensive defense structure” that reflects non-defense investments with national security implications. An intense internal debate over how to pay for these increases continues within the coalition, and the outcome is likely to be a combination of tax hikes, cuts to other government outlays, and issuance of government debt.

By any measure, the coming growth in Japanese defense spending is significant, but clear prioritization will be critical to ensuring investments that strengthen Japan’s capabilities and the alliance. The Defense Ministry’s budget request in August identified seven priority areas for additional funding—but together they are sweeping in scope, encompassing counterstrike capabilities, uncrewed systems, integrated air and missile defense, space and cyber capabilities, mobility and lift, and a catch-all resilience category that includes everything from munitions stockpiles to readiness and maintenance. Even with additional resources, this swath of requirements risks stretching the budget thin. In the near term, resilience is particularly important for strengthening Japan’s defenses—the SDF historically has been plagued by insufficient stocks of munitions and poor levels of readiness. Significant investments here would represent an immediate down payment on Japan’s commitment to strengthening deterrence.

Counterstrike

With the Liberal Democratic Party and coalition partner Komeito in apparent agreement on Japan’s need for “counterstrike” capability, the strategies will reflect a decision to move forward on this pathbreaking acquisition. Since the end of World War II, Japan has eschewed power projection capabilities, such as long-range missiles, aircraft carriers, or strategic bombers—a postwar strategy, linked to Article 9, known as exclusive self-defense (senshu bōei). Although the Japanese government asserts that the senshu bōei framework remains in place, long range cruise missiles represent a threshold capability that will fundamentally change Japan’s approach to deterrence.

In the 2018 defense strategy, Japan first decided to acquire “standoff” capabilities in the form ofanti-ship missiles to strike an adversary’s forces “attempting to invade Japan.” Japanese security planners have since concluded that such capabilities are insufficient, and that Japan needs the ability to target fixed military facilities deep within an adversary’s territory. Over the long term, Japan intends to extend the range of an indigenous ground-launched cruise missile to as much as 1,500 kilometers, and to develop air-, sea-, and submarine-launched launched variants. This process likely will extend into the 2030s, however; as an interim measure, Japan is therefore considering a request to purchase U.S.-made Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles (with a range of more than 1,600 kilometers) with the goal of deploying the capability before 2027. The prospect of a Japan that can strike back in response to an attack, at long range and on its own, would represent a significant new variable for potential adversaries in Pyongyang and Beijing, and one that would help to reinforce deterrence. It would also send a powerful signal about Japan’s status as a U.S. ally—today only the United Kingdom possesses the Tomahawk, although Australia has also announced the intent to acquire the capability.

また、日本が大韓民国(韓国)との関係を説明する際に使用する言葉にも関心が集まるだろう。東京とソウルの関係が比較的温かかった時期に発表されたNSSは、韓国を「日本の安全保障にとって地政学的に最も重要な隣国」と表現している。. . . 日本は、韓国と未来志向の重層的な関係を構築し、安全保障協力の基盤を強化する」と述べている。10年後、両国の関係はより不安定になっているが、地政学的に緊密な関係が必要であることに変わりはなく、5月に韓国のユン・ソクヨル大統領が就任して以来、バイデン政権は積極的に3国間のアジェンダを推進している。

国防予算

日本は、戦後前例のない防衛費の増額に踏み切ろうとしている。新しい戦略では、基幹防衛費とその他の「国家安全保障関連」投資の増加により、5カ年計画終了時にはGDPの2%に近づく予算軌道を確立することになりそうだ。報道では、5年間で約43兆円(現行計画比50%以上増)の基幹防衛予算が計上される可能性があるとされています。海上保安庁、一部の民間研究開発、公共インフラなど、他のカテゴリーも、国家安全保障に関わる防衛以外の投資を反映した新しい「包括的防衛構造」の一部として、総計算に含まれる可能性が高い。これらの増額分をどのように賄うかについては、連合内部で激しい議論が続いており、その結果は増税、他の政府支出の削減、国債発行の組み合わせになるようだ。

どのような指標を用いても、日本の防衛費の今後の伸びは著しいが、日本の能力と同盟を強化するための投資を確保するためには、明確な優先順位付けが重要である。防衛省が8月に発表した予算要求では、追加資金を必要とする7つの優先分野が挙げられているが、それらは対空攻撃能力、無人システム、統合防空ミサイル防衛、宇宙・サイバー能力、機動性と揚力、弾薬備蓄から準備・整備まですべてを含む回復力カテゴリーと、広範囲に及んでいる。リソースを追加しても、このような要件の広がりは、予算を薄く引き伸ばす危険性がある。自衛隊はこれまで、弾薬の在庫不足と即応性の低さに悩まされてきたのである。自衛隊は、歴史的に弾薬の在庫不足と即応性の低さに悩まされてきた。ここに多額の投資を行うことは、抑止力強化に向けた日本のコミットメントを直ちに下支えすることになる。

カウンターストライク

自民党と連立を組む公明党は、日本が「カウンターストライク」能力を必要とすることで明らかに合意しており、戦略には、この画期的な取得を前進させる決定が反映されることになる。日本は戦後、長距離ミサイルや空母、戦略爆撃機といった戦力投射能力を持たず、戦後9条と連動した専守防衛の戦略をとってきた。日本政府は専守防衛の枠組みを維持すると主張しているが、長距離巡航ミサイルは、日本の抑止力を根本的に変える閾値となる能力である。

2018年の防衛戦略では、日本はまず、「日本への侵略を試みる」敵対勢力を攻撃するために、対艦ミサイルの形で「スタンドオフ」能力を獲得することを決定した。その後、日本の安全保障プランナーは、このような能力では不十分であり、敵国の領土の奥深くにある固定された軍事施設を標的とする能力が必要であると結論付けた。長期的には、日本固有の地上発射型巡航ミサイルの射程を1,500kmまで延ばし、空、海、潜水艦から発射するタイプのミサイルを開発する予定である。しかし、このプロセスは2030年代まで続くと思われる。そこで日本は暫定措置として、2027年までの配備を目標に、米国製の陸上攻撃型巡航ミサイル「トマホーク」(射程1600キロ以上)の購入要請を検討している。日本が攻撃に対して、長距離かつ単独で反撃できるようになることは、平壌と北京の潜在的な敵対者にとって重要な新しい変数であり、抑止力の強化につながる。現在、トマホークを保有しているのはイギリスだけであるが、オーストラリアも保有を表明している。

An effective Japanese counterstrike capability would set the stage for a far deeper level of command-and-control integration with the United States than exists today. Regardless of the system Japan acquires, it will have to rely heavily on U.S. intelligence and targeting support as it develops the capability. Any scenario in which Japan is launching long-range cruise missiles at targets in China or North Korea would almost certainly coincide with U.S. military action; the allies therefore will need to develop an integrated process for target identification, prioritization, and deconfliction to maximize the effectiveness of U.S. and Japanese strike operations. This capacity does not exist today. With the counterstrike decision in place, reimagining U.S.-Japan command and control would represent the next opportunity to deepen the alliance.

Strengthening Japan’s Defense-Industrial Base and Cybersecurity

Both the national security and defense strategies are likely to include an emphasis on strengthening cybersecurity to protect Japanese government networks as well as critical infrastructure. New initiatives are likely to include efforts to strengthen the authorities of the National center of Incident readiness and Strategy For Cybersecurity (NISC), which today nominally sets cybersecurity standards and oversees incident response—or the creation of an entirely new organization, to better integrate cyber defense capabilities in the Defense Ministry and National Police Agency. The Ministry of Defense reportedly is planning to increase personnel responsible for cyber defense by a factor of five to around 4,000 personnel, from just over 800 todayby 2027. A focus in Japan on strengthening cybersecurity will be welcome in the U.S. government; weak cybersecurity practices across the Japanese government have been a critical impediment to deeper alliance cooperation and expanded information-sharing.

Finally, the defense strategy will also place a heavy emphasis on strengthening Japan’s defense-industrial base. Despite steps to loosen restrictions on defense equipment exports under Abe, Japan’s defense industry is largely uncompetitive internationally, and remains focused on the small domestic market. A recent exodus of second- and third-tier suppliers from the sector has further alarmed Japanese leaders. The defense strategy is therefore likely to advance a number of steps to strengthen the industry, including increased funding for research and development; further loosening of export rules, in particular to allow more flexibility for transfers to countries that could be parties to a conflict (current rules make it difficult for Japan to provide equipment to Ukraine, for example); and exploring new institutions, perhaps modeled on the Innovation Unit, to support and capture emerging dual-use high technologies. This is an urgent area for the Japanese government—but also a challenging one to address, given the existing structure of Japan’s industry, in which defense is a small side business for even the largest firms. The imminent announcement of a partnership among Japan, the United Kingdom, and Italy to develop a common fighter aircraft will signal Tokyo’s intent to move toward a codevelopment and co-acquisition model that diverges from the past practice. will signal Tokyo’s intent to move toward a codevelopment and co-acquisition model that diverges from the past practice.

The Kishida government’s new national security strategy represents an inflection point—one that sets in motion a material transformation in Japan’s defense posture that builds upon the policy and legal reforms that Abe put in place. These changes were unimaginable only a few years ago and represent a vast opportunity for the U.S.-Japan alliance.

Christopher B. Johnstone is the Japan Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

日本が効果的な反撃能力を持つようになれば、米国との指揮統制の統合が現在よりもはるかに深いレベルになることが予想される。日本がどのようなシステムを導入するにせよ、能力を開発する際には、米国のインテリジェンスとターゲティングのサポートに大きく依存する必要がある。日本が中国や北朝鮮の標的に長距離巡航ミサイルを発射するシナリオは、ほぼ間違いなく米国の軍事行動と重なる。したがって同盟国は、日米の攻撃作戦の効果を最大化するために、標的の特定、優先順位付け、デコンフリクションのための統合プロセスを開発しなければならない。このような能力は、現在では存在しない。反撃の決定がなされた今、日米の指揮統制を再構築することは、同盟を深化させる次の機会であるだろう。

日本の防衛産業基盤とサイバーセキュリティの強化

国家安全保障戦略と防衛戦略のいずれにおいても、日本政府のネットワークや重要なインフラを保護するためのサイバーセキュリティの強化が強調されると思われる。新たな取り組みとしては、現在、名目上、サイバーセキュリティの基準を設定し、インシデントレスポンスを監督しているNISC(National center of Incident readiness and Strategy For Cybersecurity)の権限を強化する取り組みや、全く新しい組織を設立し、防衛省や警察庁のサイバー防衛能力をより統合することが考えられる。防衛省は、2027年までにサイバー防衛の担当者を現在の800人強から5倍の4,000人程度に増やす計画だと報じられている。日本政府がサイバーセキュリティの強化に注力することは、米国政府にとっても歓迎すべきことである。日本政府全体のサイバーセキュリティの脆弱性は、同盟協力の深化や情報共有の拡大にとって決定的な障害となってきた。

最後に、防衛戦略では、日本の防衛産業基盤の強化も重視される。安倍首相の下で防衛装備品の輸出規制を緩和する措置がとられたにもかかわらず、日本の防衛産業は国際競争力がほとんどなく、小さな国内市場に焦点を当てたままである。最近、防衛産業から二流、三流のサプライヤーが流出していることが、日本の指導者をさらに不安にさせている。そのため防衛戦略では、研究開発費の増額、輸出規制のさらなる緩和、特に紛争当事国となりうる国への移転の柔軟化(現在の規制では、例えばウクライナへの装備品の提供は困難)、イノベーションユニットをモデルとした、新たなデュアルユースハイテクを支援・獲得するための新機関の検討などが、産業強化のために進められると考えられる。この分野は日本政府にとって緊急の課題であるが、防衛は大企業にとっても小さなサイドビジネスである日本の産業構造を考えると、取り組むのは困難な課題でもある。日本、英国、イタリアの3カ国が共通の戦闘機を開発するためのパートナーシップを間もなく発表することは、東京がこれまでの慣行とは異なる共同開発・共同取得モデルへ移行する意思を示すものである。

岸田外相の新国家安全保障戦略は、安倍首相が実施した政策・法改正を土台に、日本の防衛態勢に重大な変革をもたらす変曲点である。こうした変化は、ほんの数年前には想像もできなかったことであり、日米同盟にとって大きなチャンスとなる。

クリストファー・B・ジョンストン ワシントンD.C.の戦略国際問題研究センターで日本講座を担当。